Amilcar Cabral's Pedagogy of Liberation Struggle and His Influence On FRETILIN 1975-1978

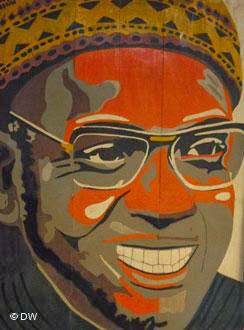

Amilcar Lopes Cabral (1924-1973) founded the Partido Africana da Independencia da Guinee e Cabo Verde (PAIGC) in 1956, and remained the head of the Party until he was tragically shot dead by Kani Inocencio, a corrupted former PAIGC comrade, in Conakry, 20 January 1973 (Chilcote 1999:xxxi). This study examines Amilcar Cabral as both a political leader and as a popular educator, and his influence on the Timorese struggle for independence. Paulo Freire, acknowledged as the leading figure in popular education in the 20th century, once commented that for Cabral, words are always in dialectical unity between action and reflection, theory and practice‘ (cited Davidson 1979:35).

George Aditjondro, a left intellectual in Indonesia, has argued that the theory and praxis of Cabral and his independence movement became a primary source of inspiration for FRETILIN. In particular, Adjitondro argues that the establishment of the women‘s wing of the party, Organizacao Popular das Mulheres de Timor (OPMT), grew out of Carmen Pereira‘s work in the liberated Zones in Guinea Bissau; and that FRETILIN‘s ideas on agriculture cooperatives and on organizing youth were also influenced by Amilcar Cabral and Paulo Freire. During my own research, two original members of the Casa dos Timores students in Lisbon confirmed Cabral‘s influence. Both Abilio Araujo and Justino Iap told me that ideas from the African liberation struggle helped the Timorese struggle, and that Amilcar Cabral ideas traveled to East Timor through the Casa dos Timores students. They told me they were indeed in contact with these ideas, and were inspired by the works of the leaders of the African liberation movements, not only Amilcar Cabral of PAIGC, but also Eduardo Mondlane of Mozambique, and Agostinho Neto of Angola (Interviews, Yap, 14/06/2008; Araujo, 09/2009).

George Aditjondro, a left intellectual in Indonesia, has argued that the theory and praxis of Cabral and his independence movement became a primary source of inspiration for FRETILIN. In particular, Adjitondro argues that the establishment of the women‘s wing of the party, Organizacao Popular das Mulheres de Timor (OPMT), grew out of Carmen Pereira‘s work in the liberated Zones in Guinea Bissau; and that FRETILIN‘s ideas on agriculture cooperatives and on organizing youth were also influenced by Amilcar Cabral and Paulo Freire. During my own research, two original members of the Casa dos Timores students in Lisbon confirmed Cabral‘s influence. Both Abilio Araujo and Justino Iap told me that ideas from the African liberation struggle helped the Timorese struggle, and that Amilcar Cabral ideas traveled to East Timor through the Casa dos Timores students. They told me they were indeed in contact with these ideas, and were inspired by the works of the leaders of the African liberation movements, not only Amilcar Cabral of PAIGC, but also Eduardo Mondlane of Mozambique, and Agostinho Neto of Angola (Interviews, Yap, 14/06/2008; Araujo, 09/2009).

This study examines Cabral‘s idea of ‗national liberation as act of culture‘, from the perspective of popular education pedagogy. The main sources consulted were:

- Patrick Chabal‘s book, Amilcar Cabral: Revolutionary Leadership and People’s War (Chabal 2003);

- Ronald H. Chilcote, National liberation against imperialism: theory and practice of revolutionary Amilcar Cabral (Chilcote 1999); and

- Return to the source: Selected speeches of Amilcar Carbral (African Information Service 1973)

It was Chilcote who introduced the term Pedagogy of National Liberation Struggle to describe Cabral‘s ideas and revolutionary practices (Chilcote 1999:75).

Theoretical basis: Class Suicide

In 1959, Amilcar Cabral abandoned his job as an agronomist in Lisbon and returned to Guinea Bissau to fight for independence of his country, a fight which he saw as an act of culture. The first challenge and premise which he put forward was that the peasantry was not a revolutionary force in Guinea. In saying this, he differentiated between physical and political force, as the peasantry was actually a great force in Guinea. They were almost the whole population and produced the nation‘s wealth. However, because there was no history of peasants‘ revolts, it was difficult to build support among the peasantry for the idea of national liberation (Chabal 2003.p.175).

Cabral‘s second premise was that some elements of the petite bourgeoisie were revolutionary. By petite bourgeoisie, he meant people working in the colonial state apparatus, the people Abilio Araujo called ‘the colonial elites’, that is, people who benefited from colonialism but were never fully integrated into the colonial system. According to Cabral, these people were trapped in the contradictions between the colonial culture and the colonized culture, with no clear interests in carrying out a revolution. (Chilcote 1999.p.174-6). Acknowledging this weakness, Cabral wrote:

But however high the degree of revolutionary consciousness of the sector of the petite bourgeoisie called to fulfill its historical function, it can not free itself from one objective reality: the petite bourgeoisie, as a service class (that is to say a class not directly involved in the process of production), does not possess the economic base to guarantee the taking over of power. In fact, history has shown that whatever the role—sometimes important—played by the individuals coming from the petite bourgeoisie in the process of a revolution, this class has never possessed political control. And it could never possesses it, since political control (the state) is based on the economic capacity of ruling class, and in the conditions of colonial and neocolonial society this capacity is retained by two entities: imperialist capital and the native working class‘ (Chabal 2003:176).

The petite bourgeoisie, according to Cabral, was a new class created by foreign domination and indispensable to the operation of colonial exploitation. But the petite bourgeoisie could never integrate itself into the foreign minority in Guinea and remained prisoner of the cultural and social contradictions imposed on it by the colonial reality, which defines it as a marginal or marginalized class. But it is on them, the petite bourgeoisie, which the PAIGC revolution should rely (Chilcote 1999:80). Cabral delivered another speech in Havana in 1966, stating that:

the alternative - to betray the revolution or to commit suicide as a class - constitutes the dilemma of the petite bourgeoise in the general framework of the national liberation struggle… (cited Chabal 2003:179).

To carry out their historical function for national liberation, the petite bourgeoise needed to undergo a process of déclassé or class suicide, in order to organize and build alliances with the farmers to fight against colonialism and imperialism (Chilcote 1999:80).

National Liberation as an act of Culture

In February 1964, eight years after its formation, PAIGC had its first Congress in Cassaca, a liberated zone in Guinea Bissau, where it lay down the foundation for the state construction of Guinea-Bissau and Cabo Verde. Antonio Tomas describes this period as building um ‘estado dentro da colonia’, literally a state inside the colony (Tomas 2007:193; my translation). The cultural action of statebuilding in the liberated zones inside Guinea will be further discussed in this study, but I will first address the issue of culture and history, to provide an overview of the theoretical underpinnings of Cabral‘s strategy.

People’s culture versus colonial culture

Amilcar Cabral delivered two important speeches on culture between the early 1970s and when he was assassinated on 20 January 1973. In a speech delivered at Syracuse University, New York, on February 20, 1970, entitled National Liberation and Culture, Cabral stated that:

A people who free themselves from foreign domination will be free culturally only if, without complexes and without underestimating the importance of positive accretions from oppressor and other cultures, they return to the upward paths of their own culture, which is nourished by the living reality of its environment, and which negates both harmful influences and any kind of subjection to foreign culture. Thus, it may be seen that if imperialist domination has the vital need to practice cultural oppression, national liberation is necessarily an act of culture (African Information Service 1973:43).

Cabral saw culture as:

an essential element of the history of a people. Culture is, perhaps, the product of this history just as a flower is the product of a plant. Like history or because it is history, culture has as its material basis the level of the forces of production and the mode of production (Ibid: 42).

According to Cabral, every society, everywhere, has both culture and history. The colonial and imperialist forces imposed cultural domination on the indigenous people, and maintained their domination through organized repression. For example, the Apartheid regime in South Africa was, to Cabral, a form of organized repression. It created a minority white dictatorship over the indigenous people. But culture is also a form of resistance against foreign domination. In a society where there is a strong indigenous cultural life, foreign domination cannot be sure of its perpetuation. Cultural resistance could be in the form of political, economic and armed resistance, depending on the internal and external factors, to contest the foreign domination, colonialism and imperialism. The character of imperialism was ‘distinct from preceeding types of foreign domination (tribal, military-aristocratic, feudal and capitalist domination in the free competition era)‘. According to Amilcar Cabral,’ the national liberation movement (against imperialism) is the organized political expression of culture of the people, who are undertaking the struggle‘ (African Information Service 1973:43).

Amilcar Cabral further reasserted his position in his speech entitled Identity and Dignity in the Context of National Liberation Struggle, delivered at Lincoln University, Pennsylvania in 15 October 1972. He argued that imperialist domination calls for cultural oppression and attempts either directly or indirectly to do away with the most important elements of the culture of the subject people. On the other hand, a people could and should keep their culture alive, despite the organized repression of their cultural life, as a basis for their liberation movement; they can still culturally resist even when their politicomilitary resistance is destroyed. Eventually, he believed, new forms of resistance - political, economic and armed - would eventually return (African Information Service 1973:57-69).

Cultural Actions in Liberated Zones

The ideas of Amilcar Cabral were transformed into concrete actions in the liberated zones in Guinea Bissau. This was documented by Patrick Chabal, professor of Lusophone African Studies at King‘s College-London, who provided extensive data about political and economic reconstruction in the liberated areas in his book, Amilcar Cabal: Revolutionary Leadership and People’s war (Chabal 2003).

Firstly, Cabral implemented the idea of the revolutionary democracy in the political sphere. Among the political measures taken was to set up the Village Committees (Comite de Tabanca). Each committee consisted of five directly elected villagers, among whom two had to be women. Each member was responsibile for a particular area: agriculture production; security and local defense; health, education and other social services; providing supplies and deliveries to the armed forces and also to provide accommodation for visiting troops to the villages; census, civil registry and accounting (Chabal 2003: 107). The Village Committees provided basic administrative infrastructure for the management of the liberated zones, increased agricultural production, and built schools and hospitals. The local traditional ethnic systems and structures had to adopt the new systems. The traditional elders were uneasy but were the first to come forward to support the programs. Later it was the liberated zones from which PAIGC obtained greatest support which contributed most to the success of the revolution against the Portuguese colonialism (Chabal 2003:108-109).

Another interesting cultural action was the establishment of agriculture cooperatives and armazens do povo (the people‘s warehouses). Cabral believed that the war in Guinea Bissau had an economic dimension (Chabal 2003:107). The economy could be a weapon of the struggle for liberation. PAIGC had to develop policies that would systematically destroy, sabotage and in any way possible dismantle the colonial economic system (Chabal 2003.p.110). Among the policies of PAIGC were to increase and diversify food cultivation - rice, maize, potatoes, manioc, beans, vegetables, bananas, cashew nuts, oranges and other fruits; and to create and develop collective farms and cooperatives for the production of certain crops (pineapples, bananas and other fruits) (Chabal 2003:111). The agricultural products were to be stored in the armazens do povo to replace Portuguese commercial networks and to compete with private shops in the Portuguese held-zones. After establishing the first armazens do povo in 1964, there were some fifteen (15) by 1968. The stores were also centres for the people to engage in barter system, replacing the monetary system of the Portuguese. Armazens do povo provided economic justice to the people by keeping the food prices low, when they were sold for money. Rice was also always available in the stores for everyone (Chabal 2003:112-113).

Aside from the successes in the agriculture cooperatives and the armazens do povo trading system, there were also challenges. PAIGC organized collectives in the few of the plantations and farms abandoned by the Portuguese (and there were very few) but with little success. Cabral then appealed to the comrades, the party leaders, to help people to organize the collective farming, extensive mutual aid and cooperatives, assuring them of the importance of this experiment to bring about a new economic order in Guinea (Chabal 2003:112). By 1969, the party was able to export rice, coconut, and kola nuts (Hoagland 1971, cited Chabal 2003:112).

The third example of cultural action implemented by Cabral was the development of social services such as basic education and health care. Cabral urged the education system to go beyond literacy and numeracy and teach students about the liberation struggle going on in the country. In 1971, Cabral stated that:

Today our primary education is political, we cannot forget this fact. From early childhood we must prepare our people to follow the struggle of the PAIGC: to teach them the basis of the struggle, the basis of the strength of our party, about the interests and values of our party…at the same time we must teach them how to read and write and account and to make progress, slowly‘ (Chabal 2003:117).

But, according to Chabal, these schools in the liberated zones were deliberately being bombed by the Portuguese causing death of innocent children. In 1970, Cabral in return threatened to take retaliatory terrorist action against the Portuguese. Other difficulties they faced were the lack of proper organization, the lack of proper teacher training, and the reluctance of some parents to allow their children to the schools, because the children were needed on the farms. PAIGC improved the quality of education by having better trained teachers, and by 1971-1972 there were more schools opened (Chabal 2003.p.115). As mentioned above, schooling in the liberated areas went beyond the teaching of literacy and numeracy. For exmple, there was one subject called ‘militant formation‘ throughout the four year-elementary schooling. The first two years they students learned political formation. In the second two years, students learned sociological and political notions such as the social and ethnic structures of Guinea, the objectives of the national liberation struggle, and the contribution of Guinean liberation struggle to world peace. The curriculum also offered history lessons which avoided the European colonial ethnocentric tradition. Instead, lesson were about the history of Guinea and Cape Verde within the African historiography, which had emerged in the 1950s and 1960s. (Chabal 2003:116-117).

Amilcar Cabral regarded political education as the development of political consciousness, not as indoctrination. Ideologically it avoided endorsing a particular political doctrine such as, for example, Marxism-Leninism. PAIGC instead believed that experience of the nationalist struggle and of the political education in the liberated areas formed the basis for the socialist ideology (Chabal 2003:117). In addition to primary schooling, PAIGC set up boarding schools which were initially for the war orphans, but were later expanded to include selected elite boys and girls from elementary schools. These new centers were intended then to promote new ways of life. By 1971 there were four centers, under the name internatos in the liberated areas with each having 100 pupils. The most interesting aspect of these schools is that the students were supposed to participate in administering the schools and in cultivating food for their own use. These schools provided the students with a sense of leadership as a foundation for the future of the independent Guinea (Chabal 2003:117).

PAIGC established only one Party School, known as Centro de Instrucao Politico-Militar (CIPM) in 1971. CIPM provided military and political training to some 200-300 members of the armed forces for period of several months, specifically intended to raise political consciousness. They included university students returned from overseas, mixed up with illiterate members of armed forces Aside from strict military training, there were also topics like colonial domination, the nature of the enemy, the situation in Africa, international affairs, the PAIGC program, the strength and the weakness of the party, the question of national unity, the problem of regionalism and tribalism and relations of armed forces with the population (Chabal 2003:118). Cabral strongly believed that the quality of Party members would determine PAICG‘s success in attaining its objectives. Cabral also urged the women to combat the restrictions imposed by Muslim teachings on women to promote the involvement of women in the Muslim practices. PAIGC promoted women‘s participation at all levels of its structure. In the Village Committee it was obligatory for two women to be on the committee (Chabal 2003:118).

A health care sector system was also established in the liberated zones. Between 1968 and 1971 PAIGC built some 117 posto sanitarios (Tomas 2007:209), some of which were mobile medical centers, or known as mobile ‗health brigade.‘ The health brigade had one female and one male nurse and was responsible for a number of villages. They operated on the principle of developing hygiene and health prevention, and to treat those of most serious cases in the liberated zones. In 1971, PAIGC had built three safe, well- equipped modern hospitals, staffed with surgeons and other specialist across the borders of Guineé and Senegal. From only one medical doctor in 1966, by 1972 PAIGC had 18 medical doctors and 20 medical assistants. There were 9 foreign doctors in 1966, and the number increased to 23 in 1972. Some of the doctors were from Cuba and some from Eastern Europe (Chabal 2003:119-120).

The fourth example of cultural action was the establishment of a people‘s judicial system in the liberated zones, which was perceived as popular and progressive justice system. This came about through PAIGC‘s experience of a situation in Forcas Armadas de Revolucao Popular (FARP) where military and political power had been concentrated in the hands of some guerrilla commanders, leading to gross abuses and arbitrary justice, (Tomas 2007:193). PAIGC therefore took decisive steps by drafting a new legal code which essentially recognized the role of the traditional system. This was followed with the establishment of tribunal do povo, the village people‘s tribunal, for minor offences such as theft, minor violence, land disputes and family matters. The Popular Tribunal had three judges selected from Village Committee members and one schoolteacher to act as court clerk. The villagers could replace the members of the judges if they were found no longer suitable for the job (Chabal 2003.p.120-121). In his speech entitled Connecting the struggles: an informal talk with the Black Americans, given in the U.S. in October 1972, Cabral told his audience:

We now have Popular Tribunals - People‘s Courts- in our country…Through the struggles we created our courts and the peasants participate by electing the courts themselves (African Information Service 1973:84).

PAIGC claimed that crimes diminished markedly after the introduction of the peoples‘ courts, and most disputes were settled without recourse to the higher regional courts. Those cases which required jail sentences were brought to zone courts. The tribunal do povo brought back the capacity for people to control their own lives that had been taken away by the colonial rule. The higher judicial system was the Tribunal de Guerra to deal with serious crimes including death penalty for espionage and murder. Yet, corporal punishment was strictly forbidden. The court instead adopted reconciliation, rehabilitation and retributive justice, rather than punishment against the Party members and members of armed forces. This way of thinking reflected Cabral‘s conviction that human nature is essentially good and always seeks for better things. Amilcar Cabral was therefore opposed to life imprisonment and death penalty (Chabal 2003:120-123).

Conclusion

The pedagogy of the liberation struggle of PAIGC, in Cabral‘s view, arose from the fact that Portuguese colonialism was also a cultural colonialism. The revolution against Portuguese colonialism was therefore essentially a cultural opposition, to build an alternative culture. The cultural resistance of the colonized people could be in the form of political, economic and armed resistance. Assuming the farmers were not revolutionaries, Cabral appealed to the petite bourgeoise to commit class suicide by forming an alliance with the farmers, in order to educate the people about the character of an alterative cul ture to that of the Portuguese colonial fascist state of Antonio Salazar. Cabral tested his theories on the ground, in the liberated areas in Guinea Bissau. He constructed an alternative culture based on the themes or concepts of revolutionary democracy; organizing agriculture cooperatives; integrating the liberation struggle into education; preventive health care through health brigade programs; and the establishment of Popular Tribunals. They were proved to be successful. Cabral‘s life was however cut short leaving his ideas and practices seem to remain a challenge to his contemporaries in Guinea Bissau and Cabo Verde.

This study of Amilcar Cabral‘s work also confirms his significant influence on FRETILIN‘s cultural values and programs from 1975 onwards. In my interviews and discussions with the Portugalbased early FRETILIN leaders such as Abilio Araujo and Justino Iap, they confirmed that Amilcar Cabral and the PAIGC had a great influence on them. I myself have been trying to re-construct the ideas and practices of cooperatives, and to build up a centre for political formation (formacao politica) in East Timor since 2003, following ideas and practices I learned initially in the Bases de Apoio in Uato-Lari between 1977-1978. Now, having done this research, I am convinced that FRETILIN had indeed drawn these ideas and practices from PAIGC and Amilcar Cabral.

My question now, having concluded this study, is this: Are the ideas and practices of Amilcar Cabral such as revolutionary democracy, agriculture cooperatives, political formation and class suicide, preventive health and health brigade, education for liberation and popular tribunal, still relevant for FRETILIN and Timor-Leste today?

Bibliography

African Information Service (Editor) 1973, Return to the Source: Selected Speeches of Amilcar Cabral. NY & London: Monthly Review Press.

Chabal, Patrick 2003, Amilcar Cabral: Revolutionary Leadership and People’s war, London: Hurst Chilcote, Ronald H. 1999, Pembebasan Nasional Menentang Imperialisme: Teori dan praktek revolusioner Amilcar Cabral, Translation published by Sahe Study Club and Yayasan Hak, Dili.

Davidson, Basil 1979, ‗Cabral on the African Revolution‘, Monthly Review, No. 31. (July August).

Tomas, Antonio 2007, O Fazedor de Utopias: Uma Biografia de Amilcar Cabral, Lisboa, Portugal:Tinta da China.

Komentar

Posting Komentar