Stand up, the real Mr. A,lkatiri

The Australian Government and media have demonised East Timor's PM without knowing all the facts, writes Helen Hill.

The Age, June 1 2006

Ever since the August 2001 elections for the Constituent Assembly in East Timor - when the longest-standing party of resistance, Fretilin, won a convincing 57 per cent of the vote against 14 other parties - I have observed among Australian embassy employees in Dili, and most Australian journalists who write about Timor, a readiness to criticise Mari Alkatiri, East Timor's Prime Minister, on grounds that show they barely know anything about him.

Ever since the August 2001 elections for the Constituent Assembly in East Timor - when the longest-standing party of resistance, Fretilin, won a convincing 57 per cent of the vote against 14 other parties - I have observed among Australian embassy employees in Dili, and most Australian journalists who write about Timor, a readiness to criticise Mari Alkatiri, East Timor's Prime Minister, on grounds that show they barely know anything about him.

The Bulletin and The Australian regularly recommend his overthrow. The week before the Fretilin congress in Dili, the ABC joined them as regular Alkatiri critics. Jim Middleton on the ABC's evening news wondered "what would happen if Alkatiri decides to resist" calls for his resignation, and uncritically put to air claims from a sacked Fretilin central committee member alleging that 80 per cent of the central committee was against the Prime Minister. A week later, after further violent episodes in Dili, we saw Maxine McKew on Lateline trying to put words into the mouths of MPs Malcolm Turnbull and Peter Garrett: "Wouldn't you say there's not much support for Alkatiri?" How could they possibly know, if all they saw were the Australian media?

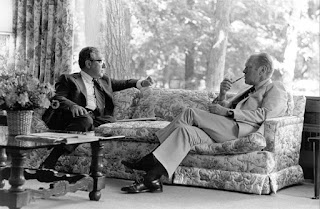

Who is Mari Alkatiri and why does he arouse such hostility from Australian politicians and media presenters? While Alkatiri was being told by Australians he should resign, he was also taking phone calls from the Portuguese and other prime ministers, wishing him well and urging him not to.

With Jose Ramos Horta, Alkatiri helped found Fretilin when, back in the early 1970s, it took the form of a clandestine group of young people meeting under the nose of the Portuguese colonialists in front of the building where he now has his office. On the eve of the full-scale Indonesian invasion, Alkatiri, who had already graduated as a surveyor in Angola, was sent with Ramos Horta and Rogerio Lobato to put Timor's case at the United Nations. His exile lasted 24 years, but it was productively used; he studied law and economics at Eduardo Mondlane University in Mozambique, with South African exiles and others struggling for freedom. Mozambique had offered scholarships to any Timorese students who could qualify for admission, and it was this group, who worked in many professions on graduating and gained a great deal of experience in economic development, who now form the backbone of the public service. In Mozambique, Alkatiri learnt a great deal about international organisations and how to avoid falling into some of the traps Mozambique had encountered. His negotiating skills that the Australian Government finds so fearsome were gained during this period.

Every year he was with Ramos Horta at the UN General Assembly for the debate on East Timor. In 1998 it was Alkatiri who did most of the thinking that led the multi-party National Council for Timorese Resistance to adopt its "Magna Carta", linking Timor's future policies with the best standards in international practice coming from the UN's conferences on human rights, environment, population, women and social development during the 1990s.

Detractors frequently allege that Alkatiri's presence in Mozambique for 24 years means he is some sort of unreconstructed Marxist. In reality, he is an economic nationalist with a strong awareness of environmental issues and woman's issues; he regularly speaks out on violence against women. He has spoken against privatisation of electricity and managed to get a "single desk" pharmaceutical store, despite initial opposition from the World Bank. He hopes a state-owned petroleum company assisted by China, Malaysia and Brazil will enable Timor to benefit more from its own oil and gas in addition to the revenue it will raise from the area shared with Australia. At the Fretilin congress, he announced initiatives for scrapping school fees in primary school and introducing state-funded meals in all schools.

There is widespread support in Timor for Alkatiri's decision not to take loans from the World Bank, although it gave Timor a few years of extremely low salaries in the public service. The Cuban doctors invited by Alkatiri to serve in rural areas are also very popular, as is the new medical school they are establishing at the national university.

The young intellectuals at the university and the leadership of many Timorese non-government organisations praise Alkatiri's economic knowledge and his ability to defend Timor's interests against the likes of the World Bank and the Australian Government (over the Timor Sea issue), while being disappointed with slow progress on educational reform and development of the co-operative sector.

His major errors of judgement include a draconian defamation law, which has drawn the ire of much of Timor's media, and his tardiness in intervening on the sacking of the dissident soldiers, in which he has supported decisions made by army commander Taur Matan Ruak.

Another frequent accusation is that Alkatiri is "arrogant", and, while this might be the case, he has increased massively the public consultations held over the last year. Under East Timor's semi-presidential constitution, the president is popularly elected while ministers are appointed by the party with the majority in the Parliament. Alkatiri has sacked some ministers for poor performance, and some of them provided support for his challenger at the Fretilin congress.

In a rather bizarre twist, one of Alkatiri's unashamed supporters during this crisis has been the World Bank, whose director wrote last week that "Timor-Leste has achieved much thanks to the country's sensible leadership and sound decision-making which have helped put in place the building blocks for a stable peace and a growing economy".

Helen Hill teaches sociology at Victoria University and is author of Stirrings of Nationalism in East Timor: Fretilin 1974-78, Oxford Press.

Komentar

Posting Komentar